In this session we will explore musical borrowing as a field of study as pioneered by the American musicologist Peter Burkholder. In considering this area, it is important to note that ‘borrowing’ and ‘quotation’ are not necessarily synonymous: a composer might use an earlier composition as a model, or ‘quote’ a phrase exactly, or paraphrase a theme so it works more appropriately in the new context. A consideration of the hypotext (the older text or texts) and the hypertext (the new text) provides a starting point for a discussion of music and meaning within these artistic spheres.

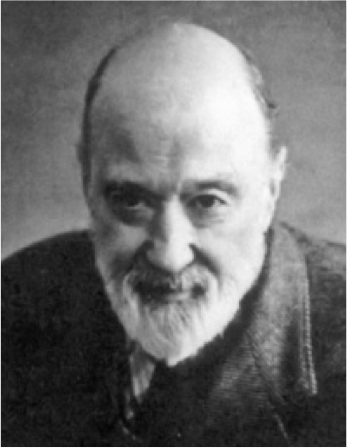

Charles Ives

The music of the American composer is often rich in quotation and reference, so it provides a good case study for our exploration. The lecture will introduce some of the terminology created and theorised by Burkholder, which is applied specifically to Ives, but has applications to a range of music types. Burkholder’s approach is summarised in the following questions:

- Analytical questions: For any individual piece, what is borrowed or used as a source? How is it used in the new work?

- Interpretive or critical questions: Why is this material borrowed and used in this way? What musical or extramusical functions does it serve?

- Historical questions: Where did the composer get the idea to do this? What is the history of the practice? Can one trace a development in the works of an individual composer, or in a musical tradition, in the ways existing material is borrowed and used?

Burkholder proceeded to develop a Typology of Musical Borrowing, which provides a useful framework for the analysis of musical borrowing in a wider range of music.

Preparation

- Read Peter Burkholder’s The Uses of Existing Music: Musical Borrowing as a Field

Associated Reading

- Peter Burkholder – “Quotation” and Paraphrase in Ives’s Second Symphony

- David Metzer – “We Boys”: Childhood in the Music of Charles Ives

Associated Listening

- Charles Ives – Central Park in the Dark

- Charles Ives – A Symphony: New England Holidays, 3rd mvt. 'Fourth of July'

- Charles Ives – Symphony No. 2 (particularly the 5th movement )

Further Resources

- Grove Music Online entry for Borrowing

- Peter Burkholder – Musical Borrowing: An Annotated Bibliography [online resource]

- Peter Burkholder – All Made of Tunes: Charles Ives and the Uses of Musical Borrowing

- Michael Talbot (ed.) – The Musical Work: Reality or Invention?

- Allan Moore – Song Means: Analysing and Interpreting Recorded Popular Music

- Justin Williams – Musical Borrowing in Hip-Hop Music: Theoretical Frameworks and Case Studies

- Olufunmilayo B. Arewa – From J.C. Bach to Hip Hop: Musical Borrowing, Copyright and Cultural Context

- Theft: A History of Music, a graphic comic tracing the history of musical borrowing

Follow-Up Work

- Construct your own one-page analysis of a chosen work, applying Burkholder’s framework. Email me an electronic version in advance of next week’s class, and be prepared to present your analysis in class