Semiology/Semiotics

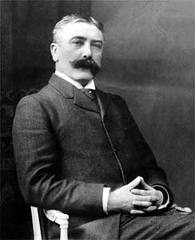

Ferdinand de Saussure

Semiology (or Semiotics) is often described, not entirely helpfully, as ‘The Science of Signs’. Our work will build on basic theories of semiology as introduced by the Swiss linguist for which David Chandler’s Semiotics for Beginners, or Jonathan Culler’s Saussure, provide good introductions. Saussure wrote, in his Course in General Linguistics (1916), that:

‘It is… possible to conceive of a science which studies the role of signs as part of social life. It would form part of social psychology, and hence of general psychology. We shall call it semiology (from the Greek semeîon, ‘sign’). It would investigate the nature of signs and the laws governing them. Since it does not yet exist, one cannot say for certain that it will exist. But it has a right to exist, a place ready for it in advance. Linguistics is only one branch of this general science. The laws which semiology will discover will be laws applicable in linguistics, and linguistics will thus be assigned to a clearly defined place in the field of human knowledge.’ (quoted in Chandler, 2012)

At the heart of Saussure’s theories is the dyadic model of the sign, comprised of a signifier (Fr. signifiant) and signified (Fr. signifié). The signifier and signified must exist together, but their relationship is arbitrary, with the signified referring to a concept, rather than (necessarily) to a materialisation. Furthermore, the relationship between signs is structural; signs only gain meaning by the difference to each other. Saussure also introduced the notion of langue – the ‘social, impersonal phenomenon of language as a system of signs’, and parole – the ‘individual, personal phenomenon of language as a series of speech acts made by a linguistic subject’ (de Saussure, 1986), which recognises the contextual nature of communication.

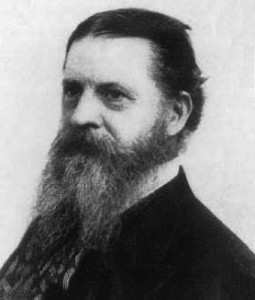

Charles Sanders Peirce

The American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce, working independently from Saussure, described a sign as ‘something which stands to somebody for something in some respect or capacity. It addresses somebody, that is, creates in the mind of that person an equivalent sign, or perhaps a more developed sign’, noting that ‘nothing is a sign unless it is interpreted as a sign.’ Peirce’s triadic system, comprising the representamen, the object, and the interpretant, is arguably more systematic and more complex than Saussure’s, but critically recognises both the role of the observer (or receiver), and the material form of the object, in the process of communication. For Peirce, semiosis is a process rather than a structure, occurring within the activity of dialogic thinking. Peirce also developed a number of typologies of semiotics, including the notions of symbolic, iconic and indexical relationships of the sign.

Note that, whilst semiology developed from linguistic and philosophical studies, there are now many branches of semiology, and many – often contradictory – approaches, each with their own set of specialist terminology. Musical semiology is a developed area of study, with a range of associated theories and analytic frameworks available for the musicologist, but one that presents particular difficulties, given the essential ‘meaningless’ of music.

Musical Semiology

The appropriation of techniques of semiological analysis for purposes of musical analysis presents the musicologist with useful critical and typological frameworks, but also poses some difficult questions. As semiological study is based on the notion of ‘meaning’ (whatever ‘meaning’ means!) or, at least, signification, its application to a field of human endeavour – music – that some theorists and composers would argue is meaningless (in that it does not, or cannot, carry meaning) might seem inherently flawed. Different views about meaning in music (or the lack of it) are held, of course, so the analyst will inevitably have to weigh up several approaches and select those which seem most applicable to the music being studied. Some comfort may be taken in the realisation that there is, as yet, no single theory of musical semiology.

Many musicologists and musical semiologists have accepted that there is a formal resemblance between linguistic systems and musical systems, and this particular approach has been the subject of much enquiry. The analogies between musical and linguistic ‘phrases’, for example, seem strong, especially if the music in question involves text setting. The rhythmic nature of poetic language, deriving from ancient Greek practices, also provides a bridge between the analysis of language and music, aided by the use of common terminology (meter, rhythm, etc.). However, it must be remembered that words are intended to convey meaning, whilst music (and what is the musical equivalent of a word?) is concerned with abstractions in sound. Care must therefore be taken when using a linguistic approach for musical analysis.

The Reading List gives some key texts in the field of musical semiology, and attention is particularly drawn to the work of Philip Tagg (especially relevant to popular music studies), who develops the concept of the museme (a minimal unit of musical meaning), first proposed by the American composer Charles Seeger in 1960. Victor Kofi Agawu (for romantic music studies) and Jean-Jacques Nattiez (whose theories are well particularly useful for the analysis of electronic and electroacoustic music) provide further frameworks for the understanding and analysis of the meaning of music and the relationships between the composer, the performer, the listener and wider society.

Musical semiology is clearly related to the field of Musical Borrowing, and to the notion of influence…

Influence

The literary theorist Harold Bloom discusses an Anxiety of Influence that has plagued poets – simply put, their relationship with their precursors have hindered their creativity. In an article entitled The ‘Anxiety of Influence’ in Twentieth-Century Music Joseph Straus writes that, ‘For Bloom, the history of poetry is the story of a struggle by newer poems against older ones, an anxious struggle to clear creative space’ (Straus, 1991, p.436).

But with some musical repertoire, others talk about a Joy of Influence. It is argued that, particularly in African American-based art forms, one celebrates the music of the past, transforming the pre-existing material in the process. This has been written about in literary theory by Henry Louis Gates Jr. as ‘Signifyin(g)’, after the tale of The Signifying Monkey. Samuel Floyd, in The Power of Black Music, has discussed Signifyin(g) in a musical context, and notes that ragtime, the blues, dixieland, swing, bebop, etc., were forms that ‘Signified’ on what came before them (and artists copied each other without lawsuits). Such Significations could be quotations of previous songs (or quoting songs in solos), or using older tunes as formal and harmonic models for new ones (such as the numerous songs based on Gershwin’s ‘I Got Rhythm’). As David Metzer writes, in Quotation and Cultural Meaning in Twentieth-Century Music:

Flourishing in both oral and written traditions, signifying takes many different forms and pursues a range of strategies. Henry Louis Gates Jr. describes signifying as “the trope of tropes,” meaning that it hosts a group of other tropes, from the classical oratorical modes of metaphor and irony to the black practices of testifying and rapping. In its myriad forms, signifying outlines the basic strategy of “repetition and revision.” Practitioners draw upon existing formal structures and concepts and continually re-work them to create new version that break away, often ironically, from the originals. [p. 49]

Associated Reading

General

- David Chandler – Semiotics: The Basics

- Bronwen Martin – Key Terms in Semiotics

Nineteenth-Century Music

- Victor Kofi Agawu – Structural Highpoints in Schumann’s Dichterliebe

- Victor Kofi Agawu – Theory and Practice in the Analysis of the Nineteenth-Century Lied

Jazz and Blues

- John P. Murphy – Jazz Improvisation: The Joy of Influence

- David Metzer – Black and White: Quotations in Duke Ellington’s ‘Black and Tan Fantasy’ in Quotation and Cultural Meaning in Twentieth-Century Music

- Ayana Smith – Blues, Criticism, and the Signifying Trickster

Twentieth-Century Popular Music

- Philip Tagg – Music’s Meanings: A Modern Musicology for Non-Musos

- Philip Tagg – Analysing popular music: theory, method and practice

- Philip Tagg – Musical Meanings, Classical and Popular: The Case of Anguish

- Philip Tagg – The Urgent Reform of Music Theory

- David Brackett – James Brown’s ‘Superbad’ and the Double-Voiced Utterance

Twentieth-Century Music

- Joseph Straus – The ‘Anxiety of Influence’ in Twentieth-Century Music

- Jean-Jaques Nattiez – Music as Discourse: Towards a Semiology of Music

- Jean-Jaques Nattiez – Reflections on the Development of Semiology in Music (long and complex, but pp. 35-40 contain a useful for a summary of the tripartite system)

- Joshua Veltman – Review of Nattiez’s Music and Discourse: Toward a Semiology of Music (a book review, but one which contains a useful, and not too complex, summary of Nattiez’s main ideas)

- Igor Stravinsky – Poetics of Music in the Form of Six Lessons

Electro-Acoustic Music

- Denis Smalley – Spectromorphology: explaining sound-shapes

- Denis Smalley – Space-form and the acousmatic image

- James O’Callaghan – Soundscape Elements in the music of Denis Smalley: negotiating the abstract and the mimetic

Associated Listening

- Duke Ellington (and Bubber Miley) – Black and Tan Fantasy (1927) (also 1929 movie footage of the tune from the film Black and Tan)

- George Gershwin (lyrics by Ira Gershwin) – ‘I Got Rhythm’ (1930). Plenty of versions can be found, but see Gershwin play a version of his own tune (c. 1934)

Internet Resources

- The Commens Dictionary of Peirce’s Terms at the University of Helsinki

- Philip Tagg’s Etymophony YouTube channel, containing many (fun!) examples of the analysis of popular music

Saussure contended that language must be considered as a social phenomenon, a structured system that can be viewed synchronically (as it exists at any particular time) and diachronically (as it changes in the course of time). He thus formalized the basic approaches to language study and asserted that the principles and methodology of each approach are distinct and mutually exclusive. He also introduced two terms that have become common currency in linguistics—“parole,” or the speech of the individual person, and “langue,” the system underlying speech activity. His distinctions proved to be mainsprings to productive linguistic research and can be regarded as starting points on the avenue of linguistics known as structuralism.