Introduction

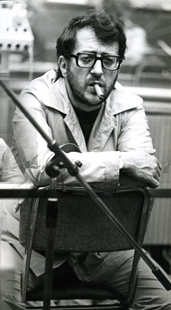

Luciano Berio in 1974 at Hilversum Radio

This session will explore the notion of music as commentary; music as a responsive act towards other musics and other stimuli. Sinfonia (1968-69) by Luciano Berio, and JazzEx (1966) by , (and other examples) will be used to illustrate the concepts, although examples will be drawn from a variety of styles and genres.

The notion of commentary in art is closely connected to the practice and development of collage. In visual art, collage is often first ascribed to the work of the Cubist painters Pablo Picasso and George Braques, and with the Dada and Surrealism movements. The combination, juxtaposition and layering of found objects (objet trouvé), often from disparate sources, has clear parallels with musical collage, and particularly with works that ‘borrow’ music from other composers. Such musical artefacts carry with them a variety of intertextual associations, and it is this act of combination that promotes the concept of commentary: one piece of music can be seen to comment on another, providing a context that may alter our understanding and apprehension of both. As Francis Fanscina writes: ‘collage is regarded … as the manifestation of a specific historical moment, a moment of crisis in consciousness’ [Oxford Art Online].

The techniques of collage arguably derive from early film making practice, and specifically the the work of the Russian director Sergei Eisenstein. Through such films as Battleship Potemkin (1925) and Alexander Nevsky (1938) and through later writings such as Film Form: Essays in Film Theory (1949), The Film Sense (1942) and Towards a Theory of Montage, Eisenstein detailed his theories of montage, maintaining that the combination or juxtaposition of two or more images made for a new whole, rather than just the sum of the parts.

Preparation

- Read Hopkins, B. – Modernism and the Collage Aesthetic

- Research ‘collage’

- Read Flynn, G. W. – Listening to Berio’s Music

- Read Osmond Smith, D. – Berio and the Art of Commentary

- Listen to Berio’s Sinfonia [plenty of other examples available on YouTube]

- Listen to Parmegiani’s JazzEx (1966), Pop’eclectic (1969), Du pop à l’âne (1969)

Class Documents

- Berio’s programme notes to Sinfonia

- The Electronic Labyrinth – Palimpsest

Class Examples

- Luciano Berio – Sinfonia | Download: Sinfonia (1968-9)

- Bernard Parmegiani – JazzEx (1966)

- Bernard Parmegiani – Pop'eclectic (1969)

- Bernard Parmegiani – Du pop à l'âne (1969)

- The Beatles – All You Need is Love (1967)

- The Beatles – Revolution 9 (1968)

- DJ Shadow – Endtroducing (1996)

Berio’s Sinfonia is perhaps the most complex work of musical commentary. Originally comprising four movements (a fifth was added in 1969, a year after its première) Sinfonia takes as its main texts the influential book The Raw and the Cooked by the French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss (see particularly myths 1, 2, 124 and 125), and the novella by Samuel Beckett, The Unnamable . The third movement, in particular, comprises a complex web of musical and textual references, based around a skeleton that uses Scherzo from Mahler’s 2nd Symphony in various states of intelligibility. Musical references include:

- Mahler – Des Antonius Von Padua Fischpredigt , from Der Knaben Wunderhorn (31m 45s)

- Mahler – Scherzo from 2nd Symphony (part 1 , part 2 ), 4th Symphony

- Debussy – La Mer

- Schoenberg – Fünf Orchesterstücke, op. 16, no. 4, ‘Peripetie’

- Stravinsky – The Rite of Spring, Agon

- Boulez – ‘Don’ from Pli Selon Pli

- Berg – Violin Concerto, Wozzeck

- Brahms – Violin Concerto, ‘4th Symphony, 4th mvmt.’

- Beethoven – 9th Symphony

- Hindemith – ‘Kammermusik no. 4, op. 36, no. 3’ , 5th mvmt.

- Ravel – La Valse, Daphnis et Chloe

- Berlioz – Symphonie Fantastique

- Strauss – Der Rosenkavalier, Acts II + III

- Webern – Kantate, op. 31

- Stockhausen – Gruppen

- Pousseur – Couleurs croisées

Further Listening

- Luciano Berio – Laborintus 2 part 1/1 | part 1/2 | part 2 (1965)

- Luciano Berio – A-Ronne | Text (1974)

- Karlheinz Stockhausen – Hymnen (1966-7, 1969)

Further Vieweing

- Arthiur Lipsett – 21-87 (1963)

Further Reading

- Osmond-Smith, D. From Myth to Music: Lévi-Strauss’s Mythologiques and Berio’s Sinfonia

- Osmond-Smith. D. 1985. Playing on Words: A Guide to Luciano Berio’s Sinfonia

- Hicks M. 1981/2. Text, Music, and Meaning in the Third Movement of Berio’s Sinfonia

- Osmond-Smith, D. (ed.). 1985. Luciano Berio – Two Interviews

- Hand, V. 1998. Laborintus II: A Neo-Avant-Garde Celebration of Dante

- Horvath, N. The “Theatre of the Ear”: Analyzing Berio’s Musical Documentary A-Ronne

- Iverson, J. 2011. Creating Space: Perception and Structure in Charles Ives’s Collages

- Kolek, A. 2013. “Finding the Proper Sequence”: Form and Narrative in the Collage Music of John Zorn

- Maconie, R. 1998. Stockhausen at 70. Through the Looking Glass

Parmegiani began to write electro-acoustic works for the concert hall in the 1960s. Violostries (1965), a dense polyphonic work in four movements for violin and tape, is constructed out of nine basic violin tones (sound cells) suggested to the composer by violinist Devy Erlih. L’instant mobile (1966) shows the emergence of Parmegiani’s preoccupation with the passing of time, an interest that led 25 years later to a series of works inspired by ideas of temporal perception. Capture éphémère (1967), one of his most successful pieces, alludes to the passing of time, as well as to the brevity and transience of sound; it is a dynamic composition in which the subject is perfectly illustrated through micro-montage. In 1971 with Pour en finir avec le pouvoir d’Orphée, a work that amounts to a confession of faith, he claims to have broken with the seductive power of repetition and the spellbinding musical fabric in which he had excelled. During this period he composed Enfer (1972), the first part of a Divine Comedy (after Dante) written in collaboration with Bayle.

It was only with the pivotal work De natura sonorum (1975) and subsequently with Dedans-Dehors (1977), however, that Parmegiani, out of a desire for rigour and abstraction, broke free of his tendency towards aural enchantment. What his music lost in charm and spontaneity it gained in meaning and compositional skill; nonetheless, the economy of his methods and the linearity of his subjects could not mask the lingering sensuality in his music. From this point on, his sound palette was modified and clarified. To some extent he abandoned massive orchestral textures in favour of a more agile kind of counterpoint. At times, however, he reverted to full-bodied and warm material, often situated in the middle or lower register. In La création du monde (1984), for example, he turned back to progressive mutations of sound material. Later works include the four Exercismes (1985–9), compositions of almost pointillist refinement; Litaniques (1987), which takes up his fascination with incantatory music; Rouge-Mort (1987), after Mérimée’s Carmen, as powerful and dramatic as its model; Le présent composé (1991), Entre-Temps (1992) and Plain-Temps (1993), highly wrought works that refer back to reflections on time; the resonant Sonare (1996); and Sons/jeux (1998). Other notable features of his music include: a sense of humour, often emphasized by punning titles; a generosity of inspiration in an almost popular vein, particularly evident in his early works; a frequent, but never banal, use of synthesized sound; and a love of the ‘material’ element.